From Newsdesk, ‘Planting 1 million mangroves in Tonga’, Talanoa in Tonga, 9 August 2023, https://talanoaotonga.to/planting-1-million-mangroves-in-tonga/

Choose language:

Several years ago, I worked with many communities throughout Tonga on disaster risk reduction and climate change issues. The good thing about working with people is that you not only get to actually see the problems they are facing in their contexts, and hear their stories firsthand, but also to see what’s going with the work of churches on the ground. Over the past 8 years, I found out through my research that climate change is still a relatively new issue at the local church level; the majority of people don’t know what climate change is, and people perceive it as an elite-level kind of issue. Church leaders have a lot of talanoa at the decision-making level and yet not many concrete actions have been happening in places where climate change most needs to be addressed.

Tonga has been employed as a case study for this final post not only because is a member of the Pacific Conference of Churches (PCC), but also we can use Tonga as a testing ground for how effective the PCC’s climate change work in a local context has been. It’s important to talk about Tonga, because according to the World Risk Report, Tonga is the second most at-risk country in the world after Vanuatu; one of the most likely to be affected by disasters caused by natural hazards and the effects of climate change.[1] After five decades of collaboration, meetings, and declarations, PCC climate initiatives have not been effective in making change at the local level. In this post, I will discuss the Tongan churches’ past and current approaches to climate change. I start with Tonga’s national context and the important milestones which Tonga has achieved in addressing climate change. It’s necessary to have some understanding of what’s going on the national level and its connection to the church sector. Next, I outline the history of the Tongan National Council of Churches and the Tonga National Forum of Church Leaders’ journey with climate change. The intention of this post is to outline what has been achieved, what are some limitations to work around, and what needs to be improved. I end by highlighting what that means for the Anglican Church in the Pacific, and its Three Tikanga model, with some recommendations on a way forward to better caring for God’s creation.

At the national level, Tonga has reached some significant milestones towards addressing climate change issues since its participation in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in July 1998. Through the leadership and guidance of the government, Tonga has successfully integrated Climate Change into the Tonga Strategic Development Framework (TSDF) 2011–2014 and 2015–2025. Also, Tonga released its Initial National Communication under the UNFCCC in 2005, its Second National Communication in 2012, and its Third National Communication in 2019.[2] Further milestones include the design of Tonga’s Climate Change Policy 2006 and 2016, accession to the Kyoto Protocol in 2008, the ratification of the Doha amendments to the Kyoto Protocol in 2018, the formulation of the Initial Joint National Action Plan on Climate Adaptation and Disaster Risk Management (JNAP) 2010–2015 and then the Second Joint National Action Plan on Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management 2018–2028. Lastly, Tonga has rolled out climate change mitigation and adaptation programs and projects throughout the nation.[3]

The significance of the National Communication Projects is that they not only provide updates to UNFCCC of climate change activities nationally, but they also strengthen the activities discussed in previous National Communication Projects. The third National Communication built on the second, and the second on the first, in other words. The Third National Communication reported that Tonga has “strengthened the national capacities, partnership and cooperation with related sectors, raised general knowledge, increased involvement of all relevant stakeholders and enhanced awareness on climate change and its impacts”.[4] For example, Tonga successfully contributed to the fulfilment of the first threshold for 55 countries to ratify the Paris Agreement as one of 60 countries which have ratified, accepted, approved or acceded to the Paris Agreement with the UNʻs Depositary.[5] According to the UN General Secretary, Ban Ki-Moon, this is an outstanding accomplishment. As he states, “This momentum is remarkable, it can sometimes take years or even decades for a treaty to enter into force…This is testament to the urgency of the crisis we all face.”[6] Tonga has also launched the Tonga Climate Change Trust Fund after many years of working towards it. This fund is designed specifically to aid local communities in alleviating the effects of climate change. In terms of capacity building, Tonga has managed to increase its attendance in training and workshops on the Building of Sustainable National Greenhouse Gas Inventory Management Systems. Tonga has also implemented the Use of the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. This is really important for the recording of gas emissions in Tonga.

The National Communication Projects provided data and information for Tonga’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) report, Climate Change Policy 2016, JNAP 2, Tonga GCF Country Programme and other project proposals. The importance of these documents cannot be overemphasised, because they provide updated, reliable and relevant information for Tonga about its climate circumstances, and its policies, activities and programmes as Tonga works towards resilience. For example, they show how many carbon emissions were released each year and how much has been reduced. Under UNFCCC’s categorisation, Tonga is a non-Annex I member country, which means that Tonga is not obligated to follow any specific greenhouse gas reduction as required by the Kyoto Protocol. Tonga, however, continues the work to lower its greenhouse gas emissions by using and promoting renewable energy resources and energy efficiency appliances.[7] Although the country has a very small contribution to the global greenhouse gas emissions, Tonga is firm in its commitment to UNFCCC’s overall objective.

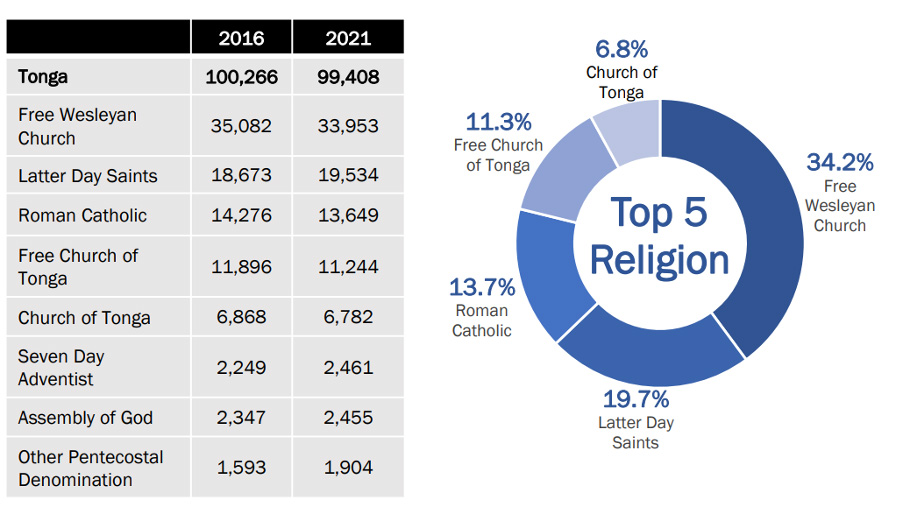

This is what the Tongan government has been doing, but what about the Tongan churches? What have they been doing in light of climate change? Tongan religious groups are diverse and comprise 13 main denominations, with further divisions within some of the denominations.[8] Figure 1 shows the numbers and proportion of adherents of the five major churches in Tonga in 2020 and 2021.

Figure 1: Religion in Tonga

(Source: Tonga Statistics Department, ‘2021 Population and Housing Factsheet’, 3)

My doctoral research found that the churches’ responses to climate change in Tonga are insufficient. In the last three decades, all churches in Tonga have done minimal work to address climate change issues, both at the denominational and ecumenical level. There are two key ecumenical bodies in Tonga: the Tonga National Council of Churches and the Tonga National Forum of Church Leaders (TNFCL).[9] TNCC is comprised of the mainline churches, which are the Roman Catholic Church, Anglican Church, Free Wesleyan Church and Church of Tonga. The TNFCL consists of all churches, including the Mormons, in Tonga.[10] In the past 4 decades of TNCC’s operation, members worked hand-in-hand on various community development projects, seminars on land issues, Cyclone Isaac recovery assistance (1982), and fundraising activities to support communities across Tonga. Despite these good works, there is still little work that TNCC has done on climate change. Like TNCC, TNFCL has done little work on climate change since its establishment in 2012. TNFCL, instead, has been focusing on some socio-political issues such as opposing the government’s ratification of The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women in 2015 and pushing to prohibit bakeries from opening on Sundays.[11] In an email correspondence with TNFCL’s General Secretary, Rev. Fili Lilo in 2017, he said that although climate change is one of the main issues on the table, it is still an issue of talanoa.[12] In my research between 2018 and 2024, climate change remains at the talanoa level. In other words, TNFCL has been active on talanoa, but less on some concrete actions on the issue. Even when the issue of Covid-19 entered Tonga, TNFCL continued the talanoa and submitted reports to the government via the cabinet.[13]

At the denominational level, a few churches have done some advocacy to address the threats climate change promises, and yet their time and effort have been stuck largely on the level of talanoa. For example, the Roman Catholic Church has responded positively to climate change through the work of Caritas Tonga, which is the arm of Catholic Church for justice, peace and development in Tonga and Niue. The main work of Caritas in relation to climate change in Tonga has been raising public awareness about the issue and its threatening impact (e.g. deforestation and rising sea levels).[14] Cardinal Soane Mafi brought together the church (the third largest in Tonga, per Figure 1) in September 2020 in a Mass; this Mass celebrated the beginning of a week dedicated to climate change.[15] Apart from this church service, there has been no other work done by the Catholic Church on climate change at the parish level.

The Anglican Church has begun some work in response to climate change. In August 2015, the Archbishop of York, Rt Hon Dr John Sentamu, joined Archbishop of Polynesia Winston Halapua, together with the Anglican community of Tonga, in an Oceanic Eucharist Service on Pangaimotu Island. This was an important part of the Anglican mission to address climate change because it was followed by the mass planting of mangrove seedlings on the part of the island where the sea has hugely eroded the land and trees have died. The environmental importance of mangroves in this place is that they help maintain the land and prevent it from eroding, and at the same time act as wave breakers, which also contributes to minimising erosion caused by waves. Additionally, a youth climate change workshop was held in Nuku‘alofa in 2017 to promote ways to build climate resilience. This was further strengthened when one of the Anglican parishes, All Saints Fasi-mo e-Afi, conducted a Community Integrated Vulnerability Assessment (CIVA) Training to equip youth to collect information about the most vulnerable people and places most at risk in times of tropical cyclones. Born out of CIVA was the Creation Care Campaign ‘No Pelesitiki’ (No Plastic). This was prompted by youth discovering large amounts of plastic waste going into the sea, where it creates a health risk for fishing grounds. Young people gather to clean up plastic rubbish on the Nuku‘alofa seashore on a regular basis, especially on Saturdays when most of the youth are available.[16] It is important to note that this work on climate change by the Anglican Church is only done by one parish and only by their youth.

The Wesleyan Church has undertaken some climate change mitigation work also. Since 2021, the Ministry of Meteorology, Energy, Information, Disaster Management, Environment, Climate Change and Communications (MEIDECC) has been working in partnership with the Free Wesleyan Church of Tonga and Sia‘atoutai Theological College via the Strengthening Adaptation Planning in Tonga Project (SAPT). This is for the ‘Development of a Climate Resilience Curriculum’ for Sia‘atoutai Theological College. The first phase of the project revised the curricula of STC to integrate climate change and ecological issues. The second phase focused on developing an accredited course module on climate change, disaster preparedness, environment, and theology. The DCRC was officially launched in July 2023 and “will be offered at Sia‘atoutai Theological College as part of its academic and ministerial curricula, along with community-based resilience training for existing church leaders and ministers”.[17]

What can we learn from these initiatives on the ground? First: they contain promise, but greater awareness and engagement is needed. The youth group in Nuku‘alofa is doing great work: what would it take to inspire other youth groups to pick up the mantle in other parts of Tonga, responding to particular local needs? What are some of the local needs—like mangrove renewal—that remain unaddressed but which could be led by local solutions, as with the mangrove replanting initiative in Pangaimotu? Informational gaps remain, too, which limit the ways people understand the climate challenges in Tonga. It’s clear that there is a need for more meteorological data to be collected; that is, data required for specialised application services such as soils’ moisture data, radiation data, and upper air data. There needs to be more rainfall measurements in various areas of the nation and more collection of ocean observations/inshore coastal water observations (e.g. tide, sea level, salinity and acidity, the absence of which makes it difficult to make proper detailed location assessments). There is a need for Indigenous/traditional knowledge and practice data to be collected. For instance, the traditional knowledge base for each community needs to be collected and stored in an accessible database which is readily available. This will help people aware of the capacity they already have and how to use it in climate adaptation and mitigation strategies. For example, there are traditional coping mechanisms for tropical cyclones (before, during, and after the event). There is also a need for impact information, especially for the delivery of better climate services. For example, GIS mapping, climate and risk profiling of every community including the collection of traditional knowledge and practices. Having better and more complete data would not only enable people to specifically aware of climate risk areas, but also the traditional coping mechanisms they have. This is essential and helpful in identifying areas to build communities’ capacity upon, as part of their response to the climate crisis.

What does all this mean for the Anglican Church, and its three-tikanga model? It shows how important it is for the churches to be involved in climate change works and to work hand-in-hand with the government and research institutes in determining and addressing environmental issues. The Anglican church in Tonga is taking the lead on the implementation of some practical initiatives on the ground—but we can do more than that. This could range from smaller initiatives to larger, joined-up initiatives. Since climate change cannot be addressed productively on an individual level in a cultural context like Tonga which thrives on and is sustained through community, it’s appropriate to approach potential solutions collectively. This is where the roles of Pacific Conferences of Churches, the Tonga National Council of Churches and Tonga Forum of Church Leaders are most needed. Instead of investing more funds on talanoa and meetings, a substantial amount of those funds and/or subsidies can be diverted into the development and implementation of practical initiatives on the local church level. This will have a twofold impact and effectiveness. Churches can start with the most climate-vulnerable areas and then move to other places of need, which are already being identified by the Tongan government. Additionally, by focussing on the local, churches will effectively contribute to the commitment to reducing carbon emissions by using less transport and fewer flights for regional/international meetings, conferences, workshops, and trainings.

In terms of the accessibility, affordability, and viability of potential solutions for Tonga, I propose two initial solutions: 1) Planting mangroves and other trees; and 2) Using indigenous knowledge/skills, goods and foods in preparation for natural disasters. The strength of these solutions is that first: people in Tonga can relate to them and won’t require highly-paid outside experts to teach them how to go about the work. Critically, churches have the resources to develop these practical initiatives and implement them if they prioritise climate change mitigation. In replanting trees, churches can work together with the government in providing human resources (especially youth groups, as the most physically active members of society) to plant mangroves and other trees in areas already identified by the government, through the Environment and Climate Change Department. That there is a shortage of people to do the planting has been known for years, but church communities can mobilise, and the PCC can establish a fund for this purpose and find ways to grow and sustain this fund for the long run. At the local level, churches can commit days to do this, even using some of allocated dates and times for normal church programs (e.g. bible studies, services, etc.) for planting trees.

Churches can also use the massive resources (like PCC, TNCC, TNFCL, and local church parishes) they own to fill in gaps in the current work of the government about climate change. For example, churches can establish a fund to collect data on indigenous/traditional knowledge and practice in preparation for natural disasters (before, during, and after). These data should be accessible via a database which is readily available to the wider public. The collection of indigenous knowledge can help promote ideas for leadership development and ongoing action in climate resilience (adaptation/mitigation) space. Taking this further, churches could put these together and create a curriculum or training programs for children and youth and then extend this to other groups in Tonga. Churches can continue to expand their sources of funding and find ways how to sustain funding options.

It’s time for the Church to get on with concrete actions rather than keep on keeping on with the talanoa and meetings. The climate crisis is not going to be combated by mere ideas and words, but also with action. Caring for God’s creation is about getting our hands dirty and sweating on—and for—the ground. Through our collective actions we inform, enrich, and improve the quality of our theories, talanoa and meetings. Words alone neither grow mangroves/trees as wave breakers and preventers of soil erosion nor build climate-proof infrastructure. Words and actions are not effective when they are treated in isolation. They have to work hand-in-hand, and it is through the weaving together of both that we will come up with better concrete and sustainable solutions for the climate crisis.

This is the last in a series of four posts. Click here for the first post: A History of Care for God’s Creation within the Church: It’s Time to Walk the Walk! Click here for the second post: Lynn White Jr. and the Origin of Care for God’s Creation in the World Council of Churches. Click here for the third post: The Pacific Conference of Churches (PCC) and Practical Initiatives Addressing the Climate Crisis.

Footnotes

1 Peter Mucke, ed., WorldRiskReport 2020; Focus: Forced Displacement and Migration (Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft And Ruhr University Bochum – Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict (IFHV), 2020), 7.

2 The National Communication on climate change issues is a vital part of the obligations of countries who have officially signed/declared their commitment under the UNFCCC. These provide regular updates on their national circumstances, greenhouse gas inventory, mitigation analysis, vulnerability/adaptation assessment, constraints, gaps/needs, and other information considered relevant to the objective of the convention in addressing climate change. This update takes the form of a report.

3 Ministry for Meteorology, Energy, Information, Disaster Management, Climate Change and Communications [MEIDECC], Kingdom of Tonga Third National Communication on Climate Change, December 2019.

4 ibid., ii.

5 The Paris Agreement entered into force on 4 November 2016, 30 days after the date on which at least 55 Parties to the Convention, accounting in total for at least an estimated 55% of the total global greenhouse gas emissions, have deposited their instruments of ratification, acceptance, approval or accession with the Depositary. Both the threshold of at least 55% Parties and 55% of the total global greenhouse gas emissions have to be met before the agreement is legally binding. This is conditional to the parties’ agreement to pursue efforts to limit global warming to 1.5°C. For more details, see ‘Paris Agreement – Status of Ratification | UNFCCC’, (accessed 20 August 2024).

6 MEIDECC, Kingdom of Tonga Third National Communication on Climate Change, 192.

7 ibid., 192.

8 Tonga Statistics Department, ‘Population and Housing Factsheet 2021’, 3

9 TNCC was established in 1973. See I. C. Campbell, Island Kingdom: Tonga Ancient and Modern (Canterbury University Press, 2001), 217; J. Conan, Pioneer Secretary of TNCC for 10 years, Questionnaires sent through email, 22 October 2023.

10 Philip Cass, ‘A Common Conception of Justice Underlies Pacific Churches’ Message on Climate Change’, Pacific Journalism Review: Te Koakoa 26, no.2 (2020), 88–101.

11 Suliana A. Mone, ‘Human Rights Treaties in the Pacific: A Case Study of the Non-Ratification of CEDAW in Tonga’ (PhD Thesis, University of Waikato, 2022).

12 See Laiseni F. C. Liava‘a, ‘Climate Change and Churches in Tonga: Hampering Factors Towards Unity’ (Master of Applied Theology Thesis, Carey Baptist College, Auckland, 2018), 24.

13 Laiseni F. C. Liava‘a, ‘Reimagining a new and unifying approach to climate resilience in Tonga’ (PhD Thesis, University of Canterbury, 2024), 30.

14 Cass, 95.

15 Ibid.

16 Julanne Clarke-Morris, ‘Tongan Anglicans Build Climate Resilience’, Anglican Taonga, 19 October 2021.

17 ‘Chief Secretary and Secretary to Cabinet, ‘Acting CEO for MEIDECC launches Reports on the Development of a Climate Resilience Curriculum for Sia’atoutai Theological College’, 11 July 2023.