The Moana Water of Life 2 conference, held at the Pacific Theological College in Suva, Fiji in August 2024, platformed scientists, theologians, educators, and church leaders, who offered profound reorientations in the way we think about power, socio-economics, indigeneity, oceanic and land geographies, and the interactions between organised religion and climate change. It is difficult to capture the complexity and the many threads of discussion—anchored first by one speaker, and then returned to and woven further by another, and another—in a short post, but the generative potential of this discussion deserves a wider audience than those fortunate enough to be present over the conference’s few days. Among the grief and existential worries expressed by those who live on land threatened by rising waters, speakers also offered concrete reasons to hope, and wonder at the power and complexity of the earth.

The theme of the conference, from lamentation to hope, suggests a spectrum (along which different speakers situated themselves) as well as directional movement. Tuvaluan theologian Tafue Lusama, from Pacific Theological College, argued that to lament is to be prophetic. Several speakers spoke of distressing and challenging events, but rather than being crushed by their destruction or destructive potential, considered the promise inherent in them. Anglican Bishop Nicholas Chamberlain from the Diocese of Lincoln mentioned that his diocese was almost insolvent in 2019. Professor Elisabeth Holland, a renowned scientist specialising in climate change and ocean systems, spoke about environmental tipping points, points after which change becomes irreversible. Yet both shifted from lamentation over these circumstances towards hope. The financial challenges of Bishop Nicholas’s diocese offered an opportunity to change for the better, and for a total reframing and reprioritising of their ecological goals. Care for the environment is now central to the work of the diocese. Professor Holland cautioned strongly about the potential realities of unchecked climate change, but alongside that lamentation she offered the potential of a tipping point for good, comprised of divestment from fossil fuels and other solutions which are being developed by scientific research.

In order to tip those balances in the right direction, many speakers talked about what actions and connections needed to be strengthened in order to make a positive difference with real impact. There was much emphasis upon the partnerships that must be forged between churches and scientists. Though some in the community—even the leaders of some churches—hold religion and science to be in opposition, that is not the case and need not be the case: creating and investing in connections between the two is a critical way forward. While there is benefit for church leaders and scientists in engaging with political processes, particularly in bodies like the United Nations’ COP, it is also clear—as Anglican Archbishop Emeritus Dr. Winston Halapua pointed out—that political lifespans are short compared with the work of the church. Because politicians’ term of influence can be brief, scientists and church leaders should be talking to corporations as well as political leaders. In addition, Anglican Archbishop Julio Murray argued that though COP is a significant body, the real work of combatting climate change doesn’t happen at its meetings. Churches also have the opportunity to communicate from within, from a cultural context that could reach climate change deniers or millenarian Christians and lead to concrete local action. Archbishop Winston urged church leaders to do something with what they have: words. And Rev. Dr. Hirini Kaa, Manukura of St John’s Theological College in Auckland, described the comfort and spiritual support provided by the Anglican Church to those impacted by the devastation of Hurricane Gabrielle in Tairawhiti in 2023.

Another strand woven from many speakers’ points was that people of all ages can contribute to the work of protecting the environment around us. Several spoke of the importance of listening to as well as guiding youth. Reverend James Bhagwan of the Methodist Church in Fiji, and General Secretary of the Pacific Council of Churches, began his talk by asking his daughter Antonia to read her published poem, itself a lament, titled ‘Don’t let my home sink like the sun’. He called for indigenous climate knowledge to be brought into the curriculum of schools, including church-run primary and secondary schools, using empowering decolonised language. He called also for theological colleges to take two particular steps. First, to prioritise climate change work, so that it will be brought to the communities where graduates will go after their training. Second, to make actions which resist or reverse climate change a part of church life in the round rather than a separate programme, recognising the interconnectedness of this work with all of religious life and practice. The seeds of hope are not tended only by the young; Anglican Archbishop of Polynesia, Sione Ulu’ilakepa, told a story about an elderly man, Mihati, who took on some of the clean-up after Cyclone Kita in Tonga in 2018. Mihati responded with openness and positivity even after his house and all of his possessions in it had been destroyed by the cyclone, and he was eager to make a contribution to his community’s survival. In addition to supporting youth, Archbishop Sione advised listening to the wisdom of those with experience and knowledge.

Speakers also stressed the importance of reframing economic models and moving away from the orthodoxies of capitalism and neo-imperialism. Rev. Dr. Cliff Bird of the Uniting Church of the Solomon Islands spoke about his work reimagining the dominant model of economic projection away from GDP and a focus on growth. The political pressure being exerted right now by mining companies, who want to extract minerals from the deep ocean, alongside the environmental impacts of historical mineral extraction and the destruction of forests, leaves us ecologically poorer and less stable; Dr. Bird argued that the economic model of market growth/GDP as a measure of the economy is weak. Sharing and reciprocity preceded capitalism, and this informed his work in formulating Reweaving the Ecological Mat (REM), published by the Pacific Council of Churches. Rev. James Bhagwan pointed out that the ocean plays an important role in absorbing carbon and in producing 50-60% of the oxygen we breathe, and yet the ocean is mapped for exploitation and as a part of an economic war for resources. Feiloakitau Tevi directed a question at those from Aotearoa: what is your role in exploiting others in the Pacific? Similarly, Dr. Paul Roughan cautioned against the neo-imperialism which is present in the Pacific, and warned about treating some legal strategies as a panacea. He pointed out the risks of naming the ocean as a person (as has been done with the Whanganui River in Aotearoa) because while this strategy appears to protect the ocean, people can be subjected to custodianships, and controlled by lawyers.

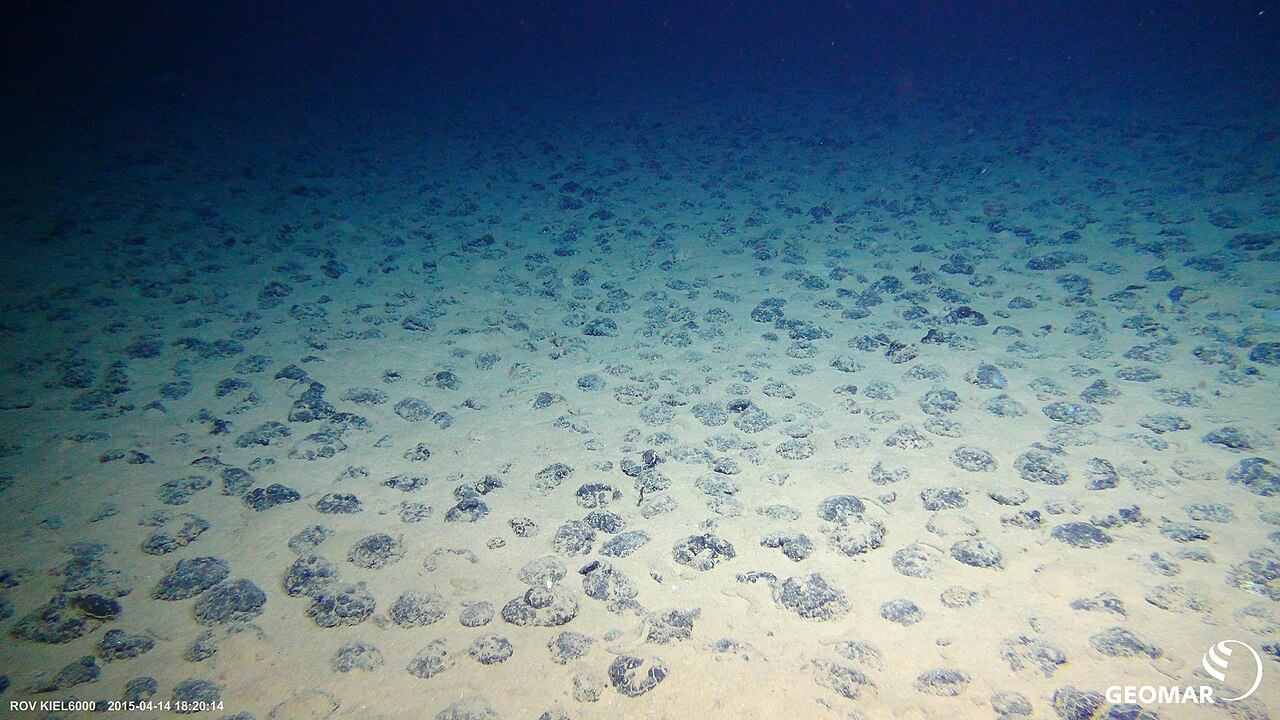

The final strand highlighted here is the power of the unknown and how an awareness of how much we do not know must temper advocates of further extraction. Taholo Kami, the United Nations’ IUCN Regional Director for Oceania and the Pacific, showed an image of nodules at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. Scientists have recently realised that these nodules are charged, and can break apart water molecules to produce oxygen deep in the ocean where light cannot reach. This ‘dark’ oxygen sits counter to the orthodoxies about the production of oxygen on our planet. Messing with these nodules—as would happen were proposed deep sea mining to proceed at scale—could have significant flow-on impacts on the health and even survival of those of us who live outside the ocean. Though there is much we cannot see or do not yet know about its systems and its depths, the ocean is central to life on land.

The Moana Water of Life 2 conference was livestreamed and can be watched here.